ADDRESSING ANXIETY IN AUTISM: WHY IT IS CRUCIAL

- Yulika Forman

- Feb 24, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 29, 2020

Most autistic children and adults experience symptoms of anxiety, even if they do not meet the clinical definition of a disorder. Just being different, not fitting in and knowing that things like talking and moving are harder for you than for others can generate anxiety. Research shows that not only unaddressed anxiety disorders but also unaddressed symptoms of anxiety in adolescents significantly increase the risk of anxiety and depressive disorders, bipolar and psychotic disorders, substance abuse and suicidal ideation in late adolescence and young adulthood.

Clearly, it is important to assess every child on the spectrum for anxiety. The focus of the assessment should be beyond anxiety disorders and include symptoms of anxiety that do not reach the criteria for a disorder.

There are three ways to think about anxiety and autism:

1) Anxiety is completely separate from autism. It looks exactly the same in people with autism as it does in others.

2) Autism increases the risk of anxiety. Difficulties in understanding the social world, or bullying, can trigger anxiety. Being overly sensitive to loud noises or other sensory input – common to autism – can make one anxious about those experiences.

3) Anxiety is simply a part of autism, driving the insistence on sameness and avoidance of social situations that are among autism's core symptoms.

There is no consensus in the field about which view might be the most accurate and helpful.

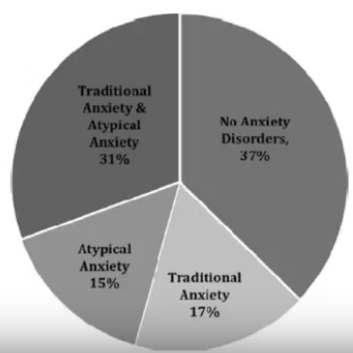

Anxiety in autistic individuals can present in a classic way described in DSM-V. Almost half of the individuals with ASD, however, also have atypical anxiety symptoms that are connected to the core symptoms of ASD and may not fit into DSM-5 categories. A third of individuals with ASD have a mix of classic and atypical symptoms.

Atypical anxiety symptoms can include:

anxiety about sensory stimuli

anxiety about upcoming transitions, possible changes in schedules or possible unexpected events;

anxiety about rule-breaking

interfering worries related to special interests; for example, worries about not having access to a special interest

phobias that have an unusual focus and are not related to sensitivity to sensory stimuli. For example, fears of graffiti, running water, mechanical objects, beards, bubbles, etc.

Social discomfort and fear of social situations without accompanying fear of being negatively viewed, judged or ridiculed. For example:

- somatic complaints in social settings

- frantic attempts to avoid and escape social settings

- aggressive and self-injurious behavior in social settings

Compulsive rigidities/rituals that are not aimed at preventing or reducing distress, achieving a “just right” feeling or preventing a dreaded event or situation; i.e. rigidities/rituals that do not serve any internal function.

The assessment of anxiety in individuals on the spectrum should include both typical and atypical symptoms. The tricky part is that traditional anxiety scales do not capture atypical anxiety. As a result, anxiety can be underestimated or overlooked in autistic individuals if traditional anxiety scales are used. There are some researchers who recognized that an anxiety scale cannot measure anxiety in a population if the population wasn't involved in its development. The group developed a Parent-rated Anxiety Scale (PARS-ASD) to measure anxiety in autistic individuals using focus groups of autistic individuals who shared their subjective experiences with anxiety.

Children on the spectrum who also have anxiety often struggle with it in school. I have had many conversations with teams about anxiety, and the answer I usually get that there is no indication of it. Autistic adults report that others don't understand their anxiety and accuse them of "making excuses" not to engage in certain activities or tasks. Why is it that anxiety is so hard to recognize and believe?

The way I found to explain this phenomenon is that there are three components to anxiety: cognitive (the thoughts going through one's mind), physical (physical sensations, such as sweaty palms or increased heartbeat), and behavioral, which is the only component that can be easily observed. The behavioral component can be compared to the tip of an iceberg, which is only visible when the cognitive and physical components become very intense. If a person's anxiety is not intense enough to show behaviorally, or if the person controls their behavior, anxiety will go unnoticed. But it will not be without high consequences to the person's mental health.

Behaviors associated with anxiety are often misunderstood as willful. In schools and on educational teams, there is often a BCBA who will discuss behavioral strategies that can be used to reduce the behaviors like aggression or "non-compliance." For a child who has anxiety, however, the behavior is often the only available way to communicate the emotion the child is experiencing and the lack of skills needed to recognize and manage it in a socially-expected way. Educational teams working with children, caregivers working with autistic adults, autistic adults living independently, and clinicians working with these groups should always consider the possible role of anxiety, as well as other factors, in what is known as "maladaptive behaviors."

I usually ask the parents to share with the team some of the ways they know that their child is getting anxious. I ask for an observation and data collection to see if an observer can see those same signs of anxiety in school, at what times and during which activities. When that data are available, it is possible to teach the child coping and self-monitoring strategies, encourage the child to notice their own anxious state and practice ways to manage it. If anxiety in school is not properly addressed, the child can develop behavioral problems and even start to refuse to go to school. Some of the behavioral indicators of anxiety in children and adults on the spectrum include:

References:

Kerns, C.M., Kendall, P.C., Berry, L. et al. Traditional and Atypical Presentations of Anxiety in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2851–2861 (2014).

Anxiety at age 15 predicts psychiatric diagnoses and suicidal ideation in late adolescence and young adulthood: results from two longitudinal studies. Sabrina Doering, Paul Lichtenstein, Christopher Gillberg, Christel M. Middeldorp, Meike Bartels, Ralf Kuja-Halkola, and Sebastian Lundström. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19: 363.

SPARK webinar on anxiety and autism featuring Dr. Antonio Hardan. (2017). (this is the source of the tip of the iceberg metaphor). [Video/DVD] New York: https://sparkforautism.org/discover_article/anxiety-and-autism/?category_selected=webinar&page=1&keywords=

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Anxiety in a Clinical Dutch Sample of Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018; 9: 50. Lieke A. M. W. Wijnhoven, Daan H. M., Creemers, Ad A. Vermulst, & Isabela Granic.

I imagine that my son on the spectrum does have anxiety, but he denies that as being true. If he is feeling what I would recognize in myself as anxiety, he is not able to verbalize it. It seems to manifest itself as extreme rigidity and shut down.

It doesn't seem like there is an easy way to respond to comments, but I wanted to say that I agree and it is one of the difficulties, that autistic individuals sometimes might not know that they are experiencing anxiety and they can't report it. So it is important for those around them to know how it manifests, so we can recognize it. Thank you so much for your comment.

it is difficult to detect anxiety in autistic subjects because they are unable or have difficulties to perceive in a conscious way this emotional condition. this is my opinion.